2002 and 2004 World Monuments Watch

The “Great Wall” refers to a series of defensive barriers erected in northern China between the fifth century B.C. and the mid-seventeenth century. Its original purpose was to deter the northern nomads who lived in modern-day Manchuria and Mongolia from invading the lands of their southern neighbors. By the time of its completion the wall stretched some 4,000 miles (6,300 kilometers) across, and today it is widely known as the largest cultural monument in the world. In fact, its immense scale has given rise to the false belief that it is visible from the moon. The Great Wall is as architecturally diverse as it is long; the sections that cut through the desert were made of rammed earth while those that navigate the mountains were built from quarried stone and baked brick. Beacon towers of various shapes, which were used for storage and communication, appear intermittently along its course, and some even contain tablets with information documenting the visits of military officials and other events that took place over the centuries.

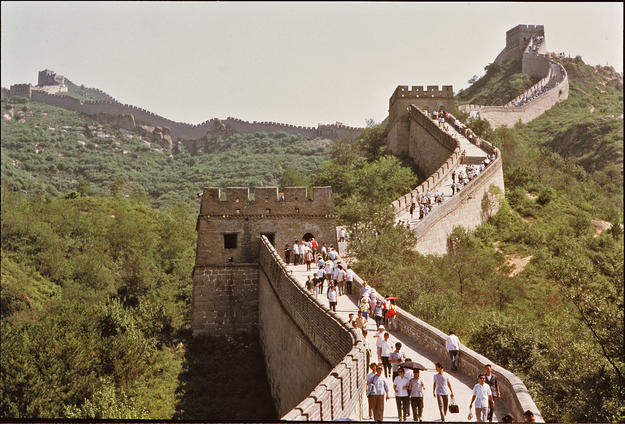

The site now attracts millions of international visitors annually, with particularly large crowds of tourists converging around 40 miles (70 kilometers) from Beijing at Badaling. In this section the wall sinks and rises dramatically in the jagged, rugged terrain. For years, stones for the Great Wall’s construction were quarried from the mountains nearby, and remnants of ancient workers’ villages still pepper the surrounding landscape today. These historic structures, as well as the Great Wall itself, were in danger of being lost due to physical deterioration and tourism-related development when the site was first included on the World Monuments Watch in 2002.

Advocacy leads to pioneering cultural heritage laws

Although the Great Wall has been a tourist destination for centuries, increased international travel in the late twentieth century created new management challenges for the site. By the year 2000, a third of the wall had eroded due to natural and man-made causes, including vandalism. After the site was selected for the 2002 Watch, we collaborated with the International Friends of the Great Wall, the Beijing Bureau for Cultural Relics, and UNESCO’s Beijing office to raise awareness of the fact that the wall is still fragile even though it has stood for centuries. As a result, interest in the issue developed both internationally and within China itself. In August 2003 Beijing officials announced the first cultural heritage laws that would protect the Badaling section of the wall, which prevented the land that surrounds it from being sold for development. During the same year the Robert W. Wilson Challenge to Conserve our Heritage funded the Huanghuacheng Pilot Project, which consisted of conservation works at a section of the Great Wall around 40 miles (60 kilometers) from Beijing. The methods used in the project included the training of locals as rangers, the establishment of a garbage and recycling center at Huanghuacheng, the removal of graffiti from the wall, a field survey and documentation of the site, and advocacy and awareness efforts in collaboration with the local press. The project as a whole may be used as an example for future interventions at the Great Wall.

Despite the manifold improvements at the wall, it was included on the 2004 Watch in order to quash the issues that remained on site. We supported the restoration of a tower in the Jiankou section of the wall in 2004, and in January 2005 the British ambassador to China held an exhibition at his home featuring photographic documentation of the site. As the 2004 Watch cycle passed, tourism-related development became an even bigger problem at the Great Wall. A new movement for more sustainable tourism along its lesser-known sections was gathering steam, and we encouraged this development with our support to a conservation project at the Wohu Shan Great Wall Reserve. In 2006 new signboards, interpretative panels, and garbage bins were added to this quiet area, funded in part by the Wilson Challenge. In December of the same year, Beijing officials announced further protective measures for the wall including a high penalty fee for anyone who defaced it.

Problems such as irresponsible tourism and physical deterioration still plague the Great Wall, but awareness of these issues has increased. In January 2016, the government of China’s Inner Mongolia region announced a five-year conservation plan for the site, including a survey and conservation of its most vulnerable sections. Such schemes must continue in the future in order to preserve this iconic monument and its surrounding historic landscape.